Published On: March 2017 in NEJM Catalyst. This article is by David S. Buck, MD, MPH & R. Conor Holton-Burke, MS. Read the story here. Available on Patient Engagement as well.

It was a hot and humid day in Houston — the oppressive sort that makes one contemplate retreating to air conditioning immediately after stepping outside. Our patients did not have that luxury.

Our group of medical professionals was the Street Outreach team for Healthcare for the Homeless–Houston (HHH), a nonprofit that provides health care, social, dental, and psychiatric services through three private clinics. With a mix of volunteers and individuals employed through HHH, our team of medical students, a doctor, a nurse practitioner, and a case manager seek to meet Houston’s homeless population where they live, visiting known communities of homeless individuals weekly to connect them to HHH services, placing them on the housing list, and helping them get the identification necessary to access services.

One way that health care providers can better serve our under-resourced patients with complex medical and social needs now is by helping them access treatments and social interventions we already know to be effective.

Sometimes, all that some patients need is a hygiene kit, a bottle of water, and some kind words. On this blistering June day, that was not the case when an overweight, middle-aged man tentatively approached. He spoke in a mumble, barely audible. His face was expressionless, but his fearful eyes darted furtively around the gazebo where the community was taking refuge from the relentless sun. Though he admitted to hearing voices, only someone trained to recognize his wandering gaze and quivering lips would recognize the traces of psychosis. His beard bore traces of grooming from a recent hospitalization for suicidal ideation, after which his diabetes medications had been stolen. Collecting his personal information to make him an appointment for the next day, I noticed that it was his birthday, wished him a happy birthday, and gave him an extra granola bar. He started crying. This man, hardened by life on the street, was brought to tears by common decency. It had been years since anyone had wished him a happy birthday.

He was perversely fortunate to be actively hallucinating, so he jumped to the top of the housing list. He was placed in emergency housing and started a relationship with a case manager. He was able to see a physician the next day, who re-prescribed his chronic diabetes and schizophrenia medications. He was offered access to a trained therapist: the elusive biopsychosocial intervention.

Most of our patients are not so fortunate. The previous week, we met a jolly woman, bronzed by constant exposure to the harsh Houston sun, who asked us for help with her lung cancer. She told us that she had had surgery several months before, but was unable to make it to her follow-up appointments. When asked about her surgery, she described how her face and arms had puffed up and reddened like a strawberry-hued marshmallow. Sure enough, when we remotely accessed her record, we learned she had been treated for superior vena cava syndrome due to an underlying squamous cell carcinoma, but she had been “lost to follow-up” prior to initiating chemotherapy. Her doctors had done everything they had been trained to do: they performed a difficult, life-saving operation and provided her with appropriate follow-up. But she couldn’t make it to her appointment, and unfortunately, she lost precious months as her disease progressed. Disheartening stories such as hers are what led Dr. Buck, the Founder of HHH, to start Houston’s Patient Care Intervention Center (PCIC), which improves health care quality and costs for under-resourced populations through data integration (social and medical) and care coordination.

Sometimes, all that some patients need is a hygiene kit, a bottle of water, and some kind words. But most of our patients are not so fortunate.

The effects of social factors on health outcomes have been well documented. Individuals from lower socioeconomic classes experience higher rates of asthma mortality, tuberculosis exposure, lung cancer, lead poisoning, obesity, life stress, and, most tellingly, all-cause mortality. Social factors are particularly acute for homeless individuals, who have a 3 to 4 fold increase in mortality compared to the general population. Housing First programs, which immediately place homeless individuals in housing, have been shown to improve overall health, decrease alcohol abuse, and lower social costs. PCIC has applied this concept to so-called superutilizers. We wanted to see if we could have similar success by addressing the social needs of those with complex medical issues, whether homeless or domiciled.

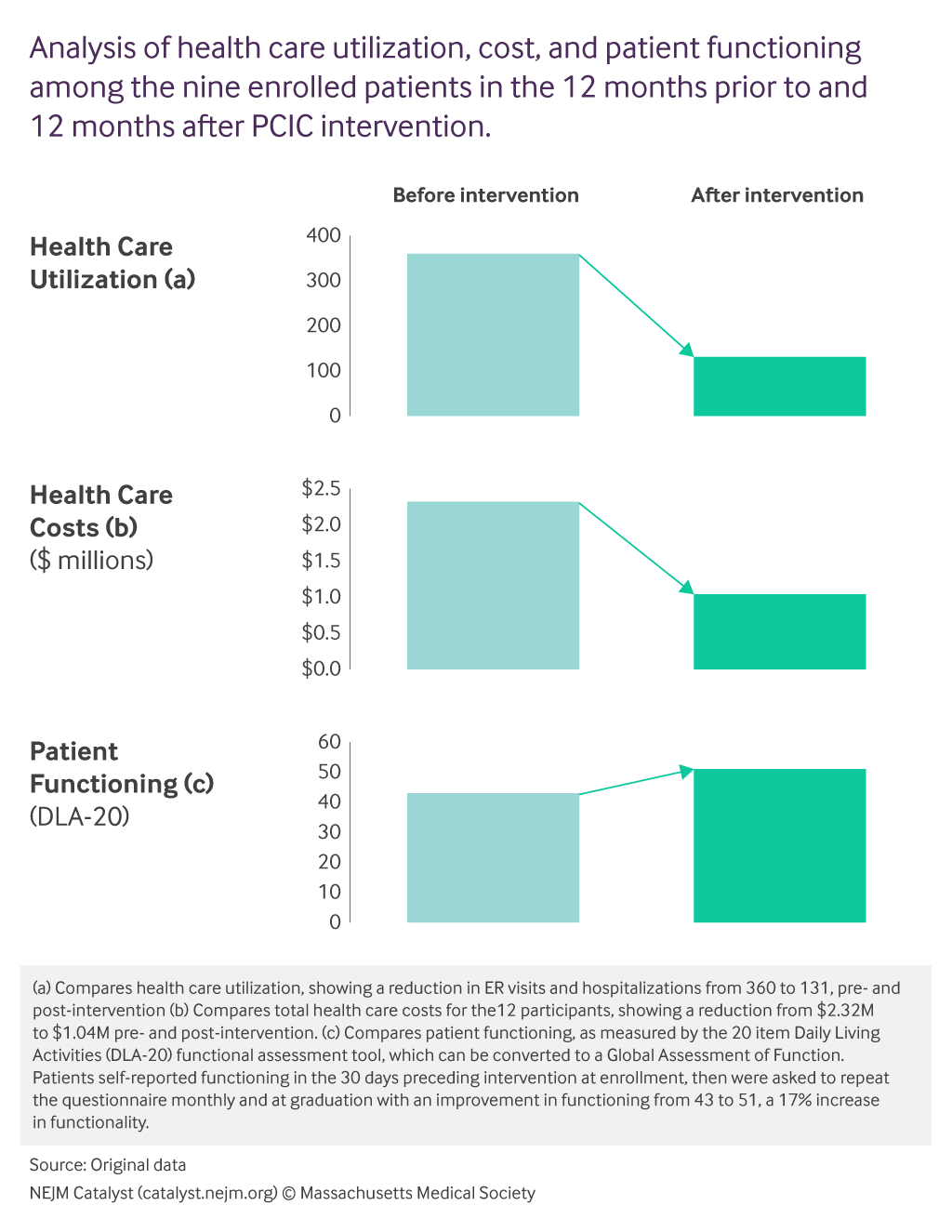

By combining data from multiple hospital systems, PCIC’s data analysts identified 39 patients in the community, who, in the previous year, had either visited the emergency room at least 10 times or been admitted at least four times. After enrollment in PCIC’s program, these patients participated in weekly meetings with care coordinators, received social assistance, and were chaperoned to primary care appointments, among other interventions. After 6 months in the program, we found that these measures decreased health care utilization, lowered total health care costs, and improved these patients’ quality of life. More specifically, the total health care costs of the 39 patients dropped from $2.3 million in the 6 months preceding the intervention to $1 million in the 6 months during the intervention. Additionally, before being enrolled in the program, the 39 patients had a combined 360 ER visits and admissions compared to 131 visits after program enrollment. Perhaps most tellingly, the patients’ self-reported functioning on the Daily Living Activities functional questionnaire (DLA-20) rose from an average of 43 to 51.

These promising initial data may represent a possible solution to social and health care problems plaguing many of our patients today, but there remains much work to be done. Longitudinal data is still being collected to determine if cost savings and life improvement continues in these patients after graduating from the program. More resources are required to determine if the data can be replicated in larger sample sizes with true control groups. Rather than focusing solely on economic impact, it may also be helpful to measure the impact of these interventions compared to other medications and social resources in a broadly applicable measure such as Quality Adjusted Life Years. Moreover, current systems lack the necessary infrastructure to effectively track health and social outcomes to determine the effectiveness of these interventions.

It will always be necessary to explore the frontiers of medical knowledge — to strive for newer, more effective treatment. One way that health care providers can better serve our under-resourced patients with complex medical and social needs now, however, is by helping them access treatments and social interventions we already know to be effective. This can only be accomplished by dedicating more research and public funds toward innovative social interventions.

Authors:

David S. Buck, MD, MPH

Professor, Family and Community Medicine, Baylor College of Medicine; President, Patient Care Intervention Center; Founder, Healthcare for the Homeless–Houston

R. Conor Holton-Burke, MS

Medical Student, Baylor College of Medicine